In March, FasterSkier recently published an article (Part I) on college ski racing in the U.S. and what a change to National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Championships might require in regards to adding a sprint race. In the second part of the series, we explore why men’s and women’s race distances are different at the collegiate and World Cup level and whether this constitutes a need for change.

***

Men | Women. Women | Men. Scanning the athletics webpage for an American institution of higher education that boasts a varsity sports team becomes a sail down the Casiquiare canal, with gender bifurcation an obligatory outcome.

Resting under the canopy of NCAA sports, however, nordic skiing presents itself as somewhat of an anomaly. Shared race days. Shared coaches. Shared course site. Shared team. At the surface level, gender in collegiate nordic skiing is almost arbitrary.

Yet, closer inspection reveals one particular area in collegiate cross country skiing where the genders differ: Race distance. In most individual nordic events at the college level, the course length of women’s and men’s races are not the same. The trend is a 5-kilometer deficit for women’s race events in comparison to men’s events.

For Molly Peters, the head nordic coach at Saint Michael’s College and former NCAA All-American in nordic skiing for Middlebury College, this is a problem.

“We’re sending a message to all the young women who have a goal to ski in college,” Peters said in a phone interview. “I just can’t imagine that they feel like their equal as people or athletes when they look and they see, ‘Oh, look every single race I’m going to be skiing 5-kilometers less.’ How are men every going to look at women equally and how are women ever going to look at themselves as being equal if you’re always skiing 5-kilometers less?”

With that in mind, Peters promised herself to reshape the sport.

“It had to be my mission in life to get it changed,” Peters said. “I feel like my best bet to get it changed is to change the NCAA Championships because everyone bases all their racing off of what the NCAA does. Every EISA [Eastern Intercollegiate Ski Association] Carnival is basically not equal because they follow whatever the NCAA does. It all trickles down.”

The Trickle Effect: One Theory on Why Race Distances Differ

A single change can create countless more. When Title IX was passed in 1972, a change was instituted in the treatment of both genders by federally funded college institutions. Within the realm of campus athletics, the alteration brought about numerous others, including an increase in the number of women participating in college sports, the scope of sports available to women and men (in certain instances, harmfully so), and perceptions of women who choose to ‘play.’

Recent Middlebury College returnee, Annie Pokorny, points out that this sort of ‘trickle down’ change should not be looked at lightly.

“When women entered sport, some rules were tweaked to account for physiological differences, but also to support the idea that athletics could be harmful to women, (particularly their reproductive systems,” Pokorny wrote in an email.

Pokorny is completing her undergraduate senior thesis on feminist philosophy and the philosophy of sport. While she admits she is not an expert, her studies and experience in nordic skiing quantify her knowledge on the subject.

Pokorny explained that myths surrounding the female body and exercise in the 20th century, caused men “to adjust sport to make it safer and more “womanly”), which turned into a conceptual connection between women and the need to protect them.”

“That conception turned into tradition, one that still thrives today in the form of shortened distances for female endurance athletes,” Pokorny added.

For Pokorny and Peters, these types of traditions were made to be broken.

“The best things that have ever happened are from people changing tradition,” Peters said. “My purpose is to get the NCAA Championships changed to be the same distance for men and women because that will trickle down to the smaller races.”

But implementing change in the NCAA Championship event and NCAA skiing is no easy task.

“NCAA skiing is comprised of a wide variety of institutions: Division I, II and III; private and public; and large and small,” Dave Stewart, head nordic coach at the University of Denver, wrote in an email. “Any choices about race format, distances, etc. must take into consideration the perspectives of this diverse group and, ideally, the decisions should be made with the goal of broadening participation at the NCAA level and increasing competition.”

If Stewart is right, the question becomes: Would making race distances equal between men and women broaden participation and increase competition?

A Second Theory & the Distance Debate: Should Men Race Shorter or Women Race Farther?

When it comes to long distance endurance events, some research argues women fare better than men.

“Women can race just as long as men,” Montana State University (MSU) incoming senior Anika Miller said on the phone. “If [the NCAA] wanted us to do a 50 k in college, sure we could do it, but it wouldn’t make any sense athletically.”

Miller — a native of McCall, Idaho, and this year’s NCAA champion in the 5 k freestyle — doesn’t doubt the ability of women to race the same distance as men.

What she questions is whether it’s necessary for women to do so.

“It’s kind of a hard conversation to have as a female athlete because you don’t want to say that women are inferior,” Miller said. “My opinion on it is that the race distances are good as they are as far as women doing a shorter distance than the men. Because time wise … for the 15 k versus the 20 k at least, sometimes the guys only race it five minutes different than the women, which isn’t really that large of a margin, [meaning] effort wise, it’s more equal.”

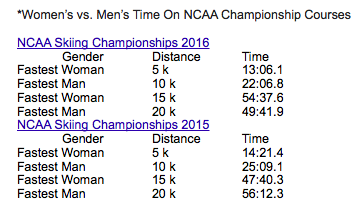

The point Miller makes is that women and men are currently racing equal. Equal amounts of time on course, at least in the 15 k and 20 k events (*see men’s and women’s course times).

Oscar Friedman, coming off his senior season at Dartmouth where he was a captain of the men’s nordic team, also argued that close to equal amounts of time on course is more important than equal course distances between men and women.

“The point of having those different race distances was to make the men’s and women’s races equally competitive,” Friedman said on the phone. “That being said, if women are internalizing it, then that’s a bigger issue. If there’s a push from within the sport, women should be the ones deciding the race distances.”

The push from women within the sport varies, but much revolves around whether women race longer or men race shorter distances. Kelsey Phinney, coming of her senior season and also a captain at Middlebury, admitted that originally the idea of equal distances didn’t appeal to her because she assumed women would be required to race farther.

“I think the misconception has been that equal distances meant that women had to race longer,” Phinney on the phone. “But it doesn’t mean that women have to go 10 k and 20 k it could mean that men go 5 k and 15 k. Or that the races range from sprints to 30 k.”

Rachel Hampton, an incoming senior at Harvard University, advocated that while women are capable of racing men’s distances, men would benefit from racing shorter lengths.

“There’s a feminist side of me that wants to say that girls can do anything boys can do and there’s no theological reason why we shouldn’t be able to race the same distance as them,” Hampton said on the phone.

“I will say I sometimes feel bad for the guys because it seems like they only race long races. I think if we added sprinting and a few 5 k races for the guys and did a wider range of distances, that would be better for them. And I think if the men were on that plan, the women could then get on the same distance plan.”

However, when men competing in college were asked if they would be willing to race the same length as women, responses were often shaped by race distances at other levels of nordic competition.

“Shortening the men’s distances would be a huge disservice because as I see it, the goal of NCAA skiing is to make American skiers as competitive as possible on the World Cup,” Friedman said. “I would be completely against shortening the men’s races. But if women want to make the call and race longer, they should fully be able to do that.”

For a few women, however, simply adjusting the women’s race lengths to match those of the men sends a certain message: Women have to be like men to be equal.

“I think the message it sends depends a lot on whether you shorten the distance of men or you increase the distance that women have to race,” Bates College ’16 grad and skier Britta Clark said on the phone. “Trying to increase the distance that we race in the name of equality, but at the same time really just saying that equality is women doing what men do, I don’t think it’s necessarily speaking to the issue.”

Clark’s point is supported by Dartmouth College Women’s Head Nordic coach and Director of Skiing Cami Thompson-Graves, also a member of the NCAA Men’s and Women’s Skiing Rules Committee, chair of the USSA Cross Country Committee, and most recently, a member of the International Ski Federation (FIS) Ladies’ Cross Country Committee.

“I don’t feel the need for women to do men’s distances,” Thompson-Graves said on the phone. “Why don’t we just do women’s distances? Why can’t we just be different … I’m a big believer in being proud to be a woman, and not a little man.”

Increasing women’s distances strikes some as a forfeiture of female identity for one that is male. Which is one reason Peters more strongly advocates for decreasing men’s distances to be the same length as women’s.

“In skiing, I think the men should come down,” Peters said. “The 20 k is really irrelevant, even at the international level. I see nothing wrong with the 5 k, I think men should do 5 k. Five k is super exciting and can be a great race. I think it should be 5 k, 10 k, 15 k, and then add in the relays and sprints.”

However, a men’s 5 k race doesn’t appear on numerous nordic race calendars — national or international — either.

“I don’t think at the national or international level men race 5 k so maybe that’s a distance skill set that would only be applicable to college skiing in the U.S.,” Raleigh Goessling, coming of his senior season at the University of New Hampshire, said on the phone. “If the race distances were changed, I feel like the distances that are contested at other levels of the sport and other formats should also play into it.”

The Window Between U.S. College Racing and the World Cup

At the international level, women and men rarely race the same distance. FIS course lengths — like the NCAA — are designed around the gender of the athletes competing.

FIS Cross-Country Committee Chair and Norwegian Olympian Vegard Ulvang indicated that similar to college racing in the U.S., FIS race distances have been different for decades. One potential reason for these differences aligns with Porkorny’s findings. According to Ulvang, how female athletes were viewed in endurance sports when they started ski racing influenced the original length of women’s race courses.

“The history behind the differences comes from the time where the nations believed that women were weaker — [with the] first female race in 1952,” Ulvang wrote in an email to FasterSkier. “Today we of course know better. Female athletes are better prepared for longer distances than men, so principally the distances should be equal.”

Principality does not always equal response. Ulvang indicated that even if the race distances should principally be equal, one major driving force for the committee to keep women’s race distances shorter than men’s rests on the race experience for spectators.

“The argument has been that the time gap between the 20 best women is bigger than that of the men,” Ulvang wrote. “Longer distances would create a ‘worse TV product’ — with one racer skiing alone [during the race].”

T.V. time does not strike Peters as an excuse for NCAA Championships and U.S. college cross-country ski schedules to follow the same format as the World Cup.

“A lot of people will say well, look at what they do at the Olympics, and look at what they do at the World Cup — it’s vastly different,” Peters said. “The women do so much less. But that doesn’t make it right. That’s a reason why NCAA follows it and EISA follows it, but that doesn’t make it right.”

Stewart, who has helped the Denver Pioneers achieve five NCAA Championship titles, supports the idea that NCAA skiing in the U.S. could act as a catalyst for change.

“As long as FIS schedules longer races for men than for women in international championships, there will be some resistance to equal distances at other levels, but I see no reason why the NCAA should not be a trendsetter and work to turn the tide on this,” Stewart wrote in an email.

He supports equal distances in cross-country skiing, seeing it as a statement that should be sport-wide, not just within NCAA nordic skiing.

“Equal distances for men and women should be implemented in our sport, both at the NCAA and international levels,” Stewart wrote. “We have had equal distances in the sports of swimming and track and field at the international and collegiate levels for many years. Equal distances would reinforce gender equity and would send the right message about our sport.”

Yet, when it comes to World Cup race lengths versus those contested at the NCAA, some argue the Championship event is already sending a message to other levels of cross country competition.

“I actually think that NCAA’s, where the women race 15 k and the men race 20 k, is much more equal than on the World Cup when the women race 15 k and the men race 30 k,” Rosie Brennan, Dartmouth grad and current U.S. Ski Team (USST) member, said on the phone.

Brennan is not opposed to a more balanced race length distribution between men and women. Her concern with changing race distances at the World Cup and NCAA collegiate level is ensuring that the racers’ performance and perspective are taken into account.

“I think it would be nice if they tried to make the [race distances] a little closer,” Brennan said. “I also think the reason the distances were different in the first place was the idea that the time the race takes should be fairly equivalent, so the effort is the same. If the time differences [between men and women] are getting to be much greater, to the point that the races are no longer requiring the same amount of effort, then I think it’s worth proposing some sort of a change and [is] something to re-visit over time.”

Brennan’s suggestion to visit the race experience for athletes doesn’t go unsupported. Men’s and women’s race distance differences have been discussed at the collegiate and World Cup level. But the actual number of times the topic has been statistically ‘re-visited’ remains a bit blurry.

Regarding conversations within the college circuit, Peters indicates that implementing changes to men’s and women’s race distances has been thrown around for some time.

“Patty Ross, who coaches at Middlebury, she’s been fighting it for 25 to 30 years and she’s had no success,” Peters said.

Ross could not be reached for comment.

Within the FIS Cross Country Committee, Ulvang indicated that the turn of the millennium was when most conversations regarding the different course lengths at the World Cup level of racing began.

“[The] question has been discussed in the FIS committee a few times the last 15 years,” Ulvang wrote.

Beyond that, four-time Olympian, USST member, Fast and Female USA President, FIS athlete rep, and now a new mother Kikkan Randall revealed that World Cup athletes have also had at least one opportunity to make their opinion about equal distances known.

“It’s an interesting topic that actually comes up quite often on the World Cup,” Randall said. “As the athlete rep to FIS, I do a survey at the end of each season and couple years ago, as part of the survey, I sent out that question [of equal distances].”

The responses Randall received found most women on the World Cup circuit — at least a few years ago — did not want to race the same distances as men.

“The majority of women actually said that they were not interested in racing the same distances as the men,” she said. “I’m considering putting that same question on the survey again this year because the comment was brought up a couple times this spring.”

And how might women racing on the World Cup respond to shortening men’s distances to make the lengths equal? The question has not been posed, but Randall may incorporate it into her next athlete poll.

“That would be another interesting take on the same question,” Randall said. “This year on the World Cup I feel like the distances were reduced a little bit with so many tour [multi-stage] events, so again it’d be an interesting time to poll the athletes and see how they feel.”

Conclusion: Connecting Part I and Part II

As long as there is snow around, colleges with nordic programs in the U.S. will continue to attract a cohort of cross-country skiers looking to compete, while simultaneously continuing their education. For many, choosing college over a club team is not the end of a cross-country skier’s long term career. It is also the potential beginning.

“The way our country is, you’re always going to have athletes choosing to go to college after high school no matter what path they’re on,” Brennan said. “So I think the more that that can be facilitated, the better it is. I mean there are a lot of good club programs that offer alternatives for people who choose that, but I think the NCAA can provide a route as well.”

Some individuals also see the NCAA as an opportunity for Americans to attend college in the U.S. and potentially compete against athletes from other countries.

“As a venue for athletes to develop into international level skiers, [the NCAA circuit] is a great place because there are really high-level skiers from all over the world in the small microcosm of NCAA skiing,” Chad Salmela, outgoing nordic coach of the College of St. Scholastica, said on the phone.

With an assured influx of athletes choosing skiing and school — and the opportunity for some to race international athletes at ‘home’ — many don’t deny the difficulty of disconnecting U.S. collegiate racing and higher levels of nordic competition.

“From a purely objective standpoint, I would say that a junior athlete who chooses to skip college (at least until they are completely done with their racing career, whenever that may be) and pursue ski racing full-time starting at age 18, is much better set up to ski faster on the World Cup level later in their career,” current USST member and former Middlebury skier Simi Hamilton wrote in an email.

“However, because of the small numbers of junior skiers we have in our country (relative to all the other skiing powerhouse nations), college is a great way to keep kids engaged and in touch with racing during a period of their lives when they may have decided they want to do something completely different,” he added.

Yet, if NCAA racing is to preserve itself as one potential path for athletes looking to make professional steps in the sport, college and World Cup racers alike agree that conversations about change — be those for adding sprinting or making race distances equal between men and women — need to continue.

“I think incorporating sprints at the NCAA is definitely worth talking about and pushing forward because that’s at least one-third of the races we do [on the World Cup], if not more,” Brennan said. “I think trying to stay current is a valuable thing.”

Ida Sargent, a Dartmouth grad and current USST member, agreed that sprinting deserves spotlight attention in present-day skiing.

“I can obviously only speak for the women’s distances but I liked how there was a short and a longer distance race,” Sargent wrote in an email regarding NCAA race distances. “I think a more important change would be adding in more sprint races. We race a sprint almost every weekend on the World Cup and when I was in college we would have one a year at the most.”

With one more year of college racing left at MSU, Miller also pushed adding more sprint races to the college race circuit to foster cross country skiers’ development.

“I think it’s unfortunate that we don’t have sprinting,” she said. “Because that’s such a great development tool.”

Though Miller and Sargent are at odds with Pokorny’s press for equal distances, all three do seem to agree that changing customs can create better opportunities and a better outlook for cross-country skiers.

- Anika Miller

- Annie Pokorny

- Bates College

- Cami Thompson-Graves

- Chad Salmela

- Dartmouth College

- David Stewart

- Denver University

- Equal Distances

- Harvard University

- Ida Sargent

- Kelsey Phinney

- middlebury college

- Molly Peters

- Montana State University

- NCAA Championships

- Rosie Brennan

- Saint Michael's College

- Title IX

- U.S. Ski Team

- Vegard Ulvang

Gabby Naranja

Gabby Naranja considers herself a true Mainer, having grown up in the northern most part of the state playing hockey and roofing houses with her five brothers. She graduated from Bates College where she ran cross-country, track, and nordic skied. She spent this past winter in Europe and is currently in Montana enjoying all that the U.S. northwest has to offer.